When Suzi Rees lost her hearing six years ago, she became curious to explore how she could adapt communication methods used in rock climbing and find new ways of working with her climbing partner that made their lives easier. In Deaf Awareness Week (4-10 May), she shares her tips for communicating with deaf climbers and what the future looks like for deaf climbing.

‘Connect and Communicate’ is the theme of this year's Deaf Awareness Week.

I stood in front of the instructor trying to lipread, take in his body language, read his facial expressions, read the rest of the group’s reactions and watch how to tie a figure 8 knot all at the same time. This doesn’t seem like a huge task until you can’t hear a single sound.

He says something about a double line, then something about a top hat, then he’s yanking around this rope attached to my harness… I sense I’m supposed to have learned how to tie this, everyone else seems to be getting it but wait… ‘What? Sorry, can you say that again please’. He repeats the instructions to the group. Great, a walking mouth. I’m still confused. This is just one big distraction to the next… I can’t keep up.

The instructor indicates for us to start climbing… ahhh bliss, at last. I reach the top… oh bugger, he’s trying to shout up something at me. ‘Sorry? What. Can you try and mime it?’ I’ve done this before. I know what to do but the way he’s gesticulating down there, it seems important. ‘Screw it’, I shout. ‘I’m coming down’.

Throughout the session, everyone is laughing and joking, there seems a good banter going on. I’m so exhausted trying to understand everyone and learn how to climb at the same time, I feel… isolated.

This was my first experience of learning to climb. Well, that’s not entirely true. My first experience was an instructor explaining that because I was deaf, it posed too great a health and safety risk to let me climb.

Deafness is one of the most widely misunderstood differences in society. Let me throw some stats at you:

-

There are an estimated 10 million deaf/hard of hearing people in the UK. That's 1 in 6 people

-

Approximately 3.5 million of those are working age individuals

-

Around 800,000 people are severely or profoundly deaf.

I think it’s fair to say that, other than Christmas with gramps, you’ll meet a deaf person at some point in your career.

Whilst communication doesn’t define the deaf community, it is one of the biggest hurdles for deaf people to access society.

When I lost my hearing some six years ago, I became curious to explore how I could adapt communication methods used in rock climbing and find new ways of working with my climbing partner that made our lives easier.

Jumping forward a number of years, I now run iDID Adventure, a social organisations improving well-being by using adventure sports as a platform to increase confidence, self-esteem and resilience in marginalised young people. At iDID, we specialise in supporting people with sensory and learning disabilities/difficulties in sports such as rock climbing, wakeboarding and snowboarding.

Our team is most recognised for its work with deaf climbers and we’ve supported countless deaf and hard of hearing people into the sport, as well as supported instructors to adapt their teaching methods by providing guidance, support and training. I’m going to share some of the common questions we receive.

How to I adapt my teaching?

Physically and cognitively, most deaf people don’t have any additional needs and learn at the same level as hearing peers. The difference is that they may need to learn in a different way.

I’m not going to bombard you with complex information about memory processing and cognition in deaf people but it’s important to point out that a large portion of learning and memory is through auditory means so our brains need to adapt to that, and as a professional, so do you.

Deafness is a broad spectrum so it’s important to ask the individual how they prefer to communicate.

Do I need to learn sign language?

Nope, it is definitely not true that all deaf people sign so you don’t need to head out to learn a new language just yet – although it is helpful if you want to work in the deaf community. What IS true is that most deaf people are very visual so it’s important, for both the instructor and the climber, to establish a visual communication system.

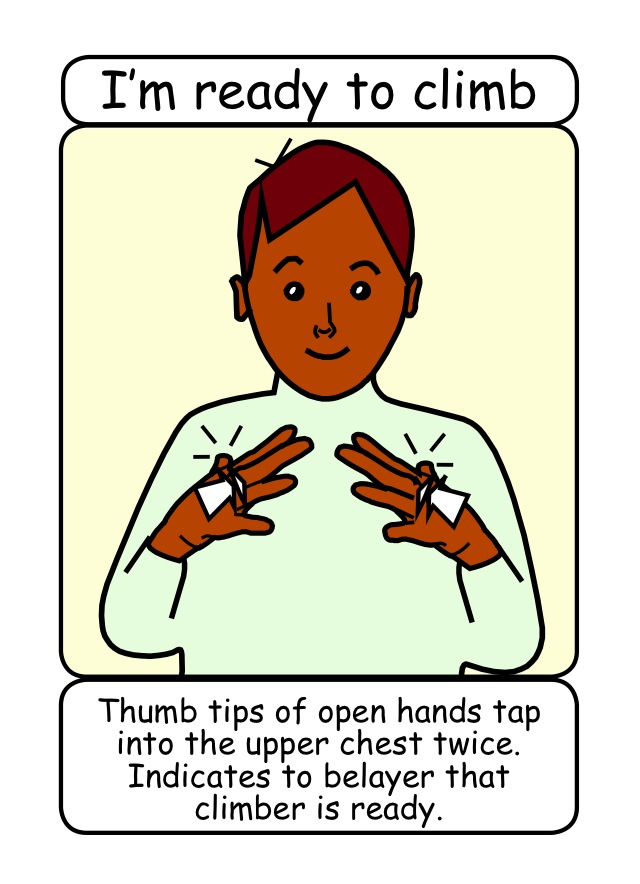

Having gone through 12 months of research, consultation and piloting, iDID developed a cross-disability communication method to improve inclusion, known as the iDID Sign Climb System. The system, a flashcard pack consisting of 10 guiding signs and 3 safety signs, aims to provide a comfort blanket to instructors… a basic set of skills to break down initial barriers and enable a safe and enjoyable experience all round. You can get in touch to find out more.

How can I be clearer?

It’s easy to forget just how complex the English language is, and superfluous too. Most of what comes out of our mouth is actually not needed so it’s actually fairly easy to be concise. Try practising how you could make your point using as few words as possible.

The speed is also important, too quick and most of it will be missed, but too slow and most of it will be distorted… and missed. 80% of lipreading is guess work which means that really, what’s coming out of your mouth is not that important. Body language and facial expressions are not just add ons, they are vital communication tools for deaf people that is why it is essential to face your climber when talking.

I advise people to speak as though they were reading a book; add emotion where it belongs, speak purposefully and use appropriate facial expression.

How do I get a deaf person's attention?

Believe it or not, this is where hearing people tend to get a bit prudish. Us English folk don’t like to be rude but sometimes you have to break the social norms to achieve something. When I’m working in a group, you’ll see me sometimes stomping my foot, waving my hands in someone face, tapping shoulders, banging on the wall or switching the lights on and off. For deaf people, this isn’t a rude thing, it’s a way of getting your climber/group’s attention.

When there is a climber on the wall, you can try and swing the rope firmly sideways (don’t try and wiggle it, it feels no different). It is important to practice this at low level so your climber knows what to feel for, that way, when it happens they know you need their attention.

Some climbers will be able to hear some sounds and may respond well to vibrations. It can be effective to bang the wall really hard. Be prepared for everyone in the centre to stop and stare!

Do I need any resources?

This is actually where you can have the biggest impact of the learning and development of a deaf climber. As we mentioned before, visual learning is best. For climbing terminology, coaching advice, safety details and equipment information, it is best to create an information pack.

Really, this should be part of your best practise and quality assurance procedures anyway. Doing this enhances everyone’s learning, not just deaf people.

What does the future look like for deaf climbing?

Earlier, I used the word ‘difference’, this is really important. Without getting controversial, there are deaf people who consider themselves as having a disability and those who do not. Those who don’t tend to be known as part of the deaf, or signing community, a cultural group with its own recognised language: British Sign Language.

It’s fair to say that at iDID, we support those who may consider themselves to have a disability. Mainly this is due to psychological barriers. We realised that because of this, we weren’t engaging the deaf community and personally, this is something I wanted to address.

From a leadership level, Paraclimbing has received a lot of attention (and rightly so!) and has been paramount in the growth of adaptive methods but it doesn’t represent deaf climbers for a number of reasons. I’ll boil them down:

-

There are not enough deaf climbers involved in the competition

-

Deaf climbers cannot be selected for the GB Paraclimbing team because there is no international category for deaf climbers

-

As far as I am aware, there isn’t enough representation for deaf climbers on the Equity and Steering board of the BMC nor the IFSC Paraclimbing board.

-

Climbing isn’t seen as a mainstream sport so deaf people aren’t always aware of it as an option

As a result, Deaf Climbing UK was set up by myself, Georgia Pilkington and Ella Gadsby. The organisation is now in development as a means to improve access and participation specifically for the deaf community. It is early days but with such a supportive community of climbers, I feel confident about its future.

Susanne Rees is co-founder of Deaf Climbing UK and CEO of iDID Adventure, a social organisation improving well-being by using adventure sports as a platform to increase confidence, self-esteem and resilience in marginalised young people. Amongst it's work, iDID supports deaf people and climbing instructors to remove some of the barriers faced by communication difficulties.

Find out more about iDID:

The iDID Sign Climb System is available in a flash pack set to purchase for a small cost, alongside free video clips explaining how to use them.

Website: www.ididadventure.co.uk

Email: info@ididadventure.co.uk

Twitter: @iDID_Online

Facebook: iDID

Find out about Deaf Climbing UK on Facebook: Deaf Climbing UK

Learn more about working with deaf people:

Do you work with, or would like to work with, deaf people? There are courses available to help you to make your sessions more deaf friendly – go to National Deaf Children's Society.

« Back