Rob Collister looks at what’s involved with leadership in the mountains.

As guides we are paid to lead. But that means far more than being first on the rope or breaking trail in deep snow. In many guiding situations today, be it an 8000 metre peak, a high altitude trek, an alpine ski tour or an ML training course, group management is as important as technical skill.

The ability to create a team out of a group of disparate individuals and to be aware of their differing needs and changing feelings is a crucial part of our job. Upon it depends not only the enjoyment of our clients and their repeat business, but often their (and our) safety as well.

Technical skills and people skills

As guides we need to be:

Respected for our technical skills - our climbing and skiing competence, our physical fitness, and our experience and knowledge reflected in an air of confidence;

Lliked for our people skills - our interest in people as individuals, our attempt to achieve Carl Rogers’ “unconditional positive regard”, our readiness to notice tone of voice and body language, and to act tactfully and discreetly on what we notice.

The traditional view was that “leaders are born, not made”; a forceful personality allied to technical skills was sufficient. Nowadays, it is widely accepted that leaders of that type are definitely limited in their effectiveness and can be total disasters.

Scott and Shackleton provide a fascinating contrast in leadership style and effectiveness, despite coming from similar naval backgrounds and leading similar bodies of men. Both were “strong” personalities, both were respected, but only Shackleton was liked by his men ....

However, although it is important for forceful personalities, the “natural” leaders, to develop their people skills, it is also possible, indeed common, for less forceful personalities to become effective leaders in situations where their experience and technical skills give them added confidence. Guiding is an obvious example.

Leadership styles

It is useful to recognize that we all have a preferred style of leadership somewhere on a continuum running from Authoritarian at one end to Democratic at the other. Overbearing behaviour, a desire to always be in front and a reluctance to listen to others are symptomatic of one extreme, while a reluctance to make decisions or impose oneself on a group are typical of the other. Both are likely to stem from a lack of confidence and neither make for effective leadership. Most of us will operate somewhere in the middle much of the time, but it is vital to be flexible - a blizzard is not the time for discussion any more than a planning meeting over a beer is the occasion for insisting on pre-determined ideas.

This view of leadership was elaborated on by Tannenbaum and Schmidt in a well-known model illustrating styles of decision-making. Leaders may choose to:

TELL, SELL, CONSULT, SHARE or DELEGATE

in their dealings with those they lead. In a mountain context it is important for a guide to be able to vary his or her style along this continuum, not only to suit the situation, but also to suit the needs of individuals. Some will feel under-valued if they are not allowed to have an input; others will feel that they are on holiday from decision-making or that they have no spare energy at that particular moment. Some will relish a role or responsibility; others will shy away from the idea. People need to be treated and communicated with as individuals as well as members of a group: obvious, but often overlooked, particularly with quiet people.

Leaders and Teams

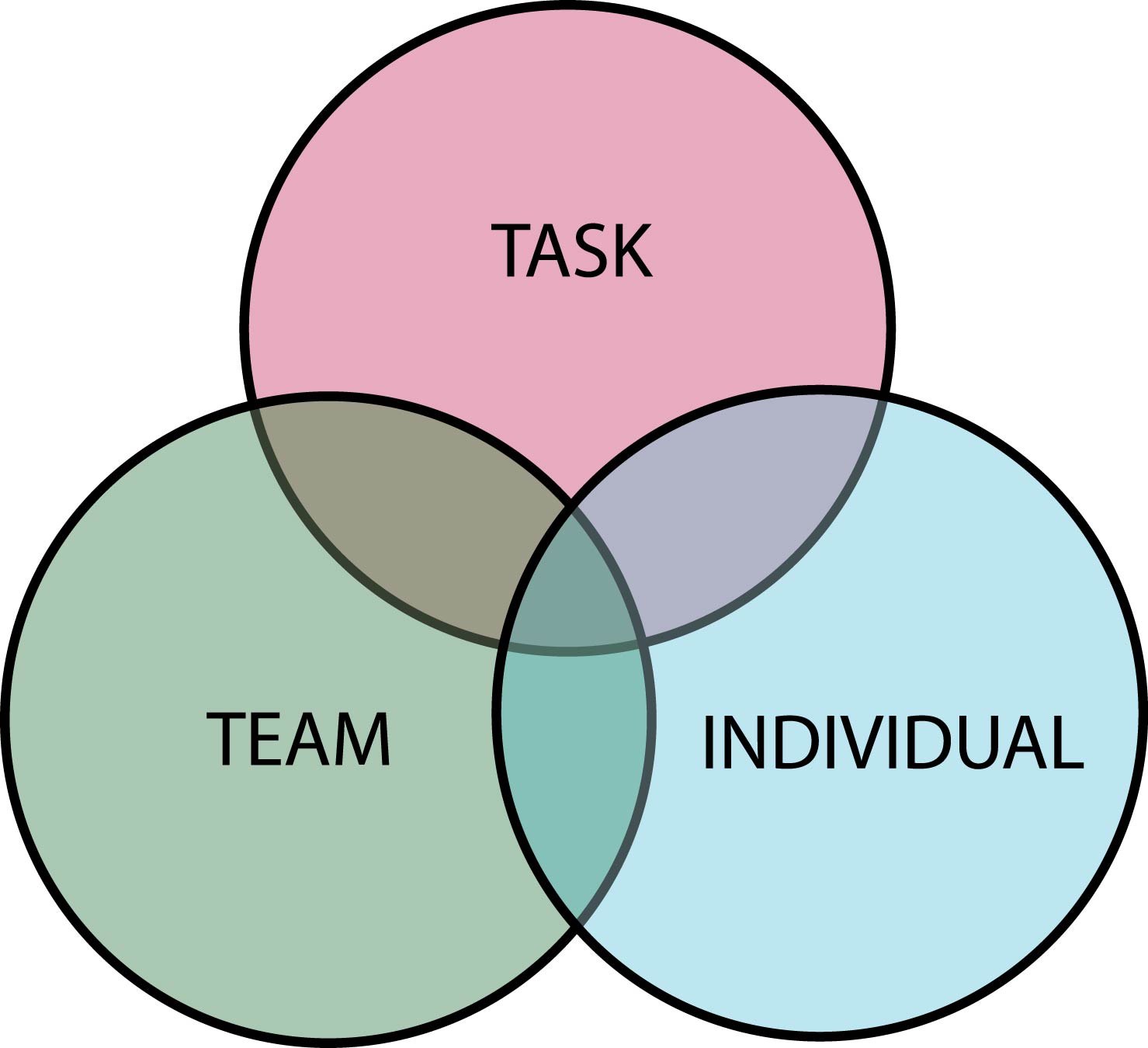

Another useful model, one of the earliest and simplest to emerge from management training, is John Adair’s Three Circles.

He suggested that the role of a leader is to balance the interlocking needs of the task in hand, the team and the individuals within it. Too often, he felt, the need to accomplish the task becomes the over-riding concern until the team feels put upon and fragments into a group of de-motivated individuals, making the task that much harder to achieve. Synergy, which makes a group so much more powerful than the sum of its parts, is lost, or never achieved.

Doug Scott has often commented on this in relation to expeditions. When personal ambition or obsession with a goal prevents the formation of a strong, mutually-supportive team, the chances of success are diminished and the likelihood of an accident increased. Events on Everest over the last few years have borne him out. Scott’s expeditions are usually leaderless, by choice, and the harmony he seeks does not always materialize, despite his efforts.

As guides we are in a better position to create a team, deliberately influencing what happens. Needless to say, it is critical that we never allow our own desires or ambitions to cloud our judgement of what individual clients are capable of or to impede the building of a strong team.

Creating a team

Our technical skills should enable us to select and achieve an appropriate objective, other factors permitting. Our people skills should enable us to respect and respond to the needs of individuals and to be alert to changes of behaviour that could be significant (in bad weather, or at altitude, especially). But how do we go about consciously creating a team?

Some groups do seem to gel better than others; but how we behave, right from the start, is the key factor. For instance:

- talking to everyone individually as early as possible;

- making sure no-one is excluded when socializing;

- keeping everyone informed by regular meetings or briefings;

- recognizing the strengths of others and using them (provided they are willing!) e.g. as linguists, cooks, trail-breakers;

- delegating jobs in camp or unguarded huts e.g. stove-lighting, chopping wood, fetching water, clearing up;

- adopting a supervisory role, rather than trying to do everything ourselves;

- encouraging people to help each other, rather than always looking to us;

- inviting feed-back and accepting criticism if offered;

- avoiding public reprimands, which can be humiliating;

- recognising that we, too, are part of the team.

The sign of a healthy team is a lack of overt leadership much of the time; jobs appear to just get done without pressure. However, that stage is not reached immediately and it is helpful to recognize that there are definite stages that a group can go through. These have been described as:

FORMING, STORMING, NORMING, PERFORMING

Not every group will go through every stage, but it can help to know that a certain amount of initial conflict can lead to a stronger, more aware team in the end.

Motivation

Another well-known model that is relevant to our work is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, which he expresses as a pyramid. At its base are those basic physiological needs which must be met if we are to survive. At its apex are those rare moments he calls “peak experiences” when individuals transcend their egos to connect with something much bigger. In between are the needs for security and shelter, the need for love, companionship and community, the need for self-esteem and recognition, and the need to fulfil one’s potential or become “self-actualising”.

.jpg)

Each particular level can only be attended to when the needs of the one below have been satisfied, and we quickly regress to a lower level when circumstances change. At its simplest, personal achievement becomes meaningless if we are starving; and it will be hard to build a team if individuals feel threatened, physically or emotionally. We need to recognize that our clients’ motivation, their desire to be with us in the mountains, usually stems from one of their higher levels of need, but if they are to satisfy it (however temporarily), we have to ensure that their more basic needs are also met. For instance, if we fail to create a happy team and instead are leading a group characterized by bickering and selfish behaviour, it is quite likely that we will fail in our objective, to the disappointment of those looking for achievement or recognition, and we will certainly not provide an atmosphere conducive to a “wilderness experience” or those fleeting moments of unity or loss of self that some of our clients may be seeking.

Difficult situations

1. Conflict

In any group, sooner or later a situation will arise that needs confronting or conflict will occur between individuals or between one or more individuals and the leader. How it is handled determines not only the leader’s credibility, but whether the team becomes stronger or weaker as a result.

Key to this is the ability to remain assertive without becoming either passive or aggressive (or passive-aggressive). Maintaining an assertive position depends on awareness of the messages we are sending by our posture and tone of voice as well as care with the choice and phrasing of the words we use. Also central is distinguishing between criticism of behaviour and criticism of the person. Behaviour can be altered, personality cannot. Behaviour may be unacceptable and we must say so, but we reject or judge the person at our peril.

2. Fear

How we handle fear, sometimes our own but more often that of others, is another aspect of leadership in mountains. Our own behaviour and demeanour are all-important. If we can appear relaxed and confident, even in a gnarly situation, it will reduce or dispel anxiety in the group. Tension is the last thing we want, especially when skiing. We need to be aware of how powerfully suggestive language can be, e.g. “It’s important not to fall here” will ensure that that is precisely what happens. It is worth developing a repertoire of jokes, stories or games for distracting attention or lightening a situation; and, conversely, ways of focussing attention when needed - deep-breathing, visualisation etc.

Conclusion

For a skill on which our success or failure as guides depends, most of us pay remarkably little attention to how we lead or to how we might develop as leaders. This article does no more than skate over the surface of some huge areas of knowledge and research, and introduce a few relevant models; but if it encourages guides to make their leadership a more conscious and considered process, it will have served a useful function.

« Back