The digital age is upon us, not least in the world of expeditions where digital mapping is easily at our fingertips. So how on (google) earth can online mapping be used to plan remote expeditions? We tap into the expert knowledge of mountaineer George Cave to explain the basics.

Shortly after leaving university, I started planning my first expedition beyond the Alps. In the UK and Europe we are blessed with easy access to incredibly accurate and detailed maps (in fact, the entire Ordnance Survey coverage of the UK can be browsed online for free at Bing Maps). But what about access to maps for the lesser traveled parts of the world?

Initially concerned that navigating the unclimbed mountains of central Asia might require a David Livingstone-esque leap of faith, I turned to the internet. Fortunately these days two of the largest and best sets of world maps are freely available for anyone to access online, and here’s how.

Google Earth

Google provide two free mapping tools, the most familiar being the web-based Google Maps interface. However for expedition planning it is far simpler to use Google Earth, a separate, standalone program which can be downloaded free.

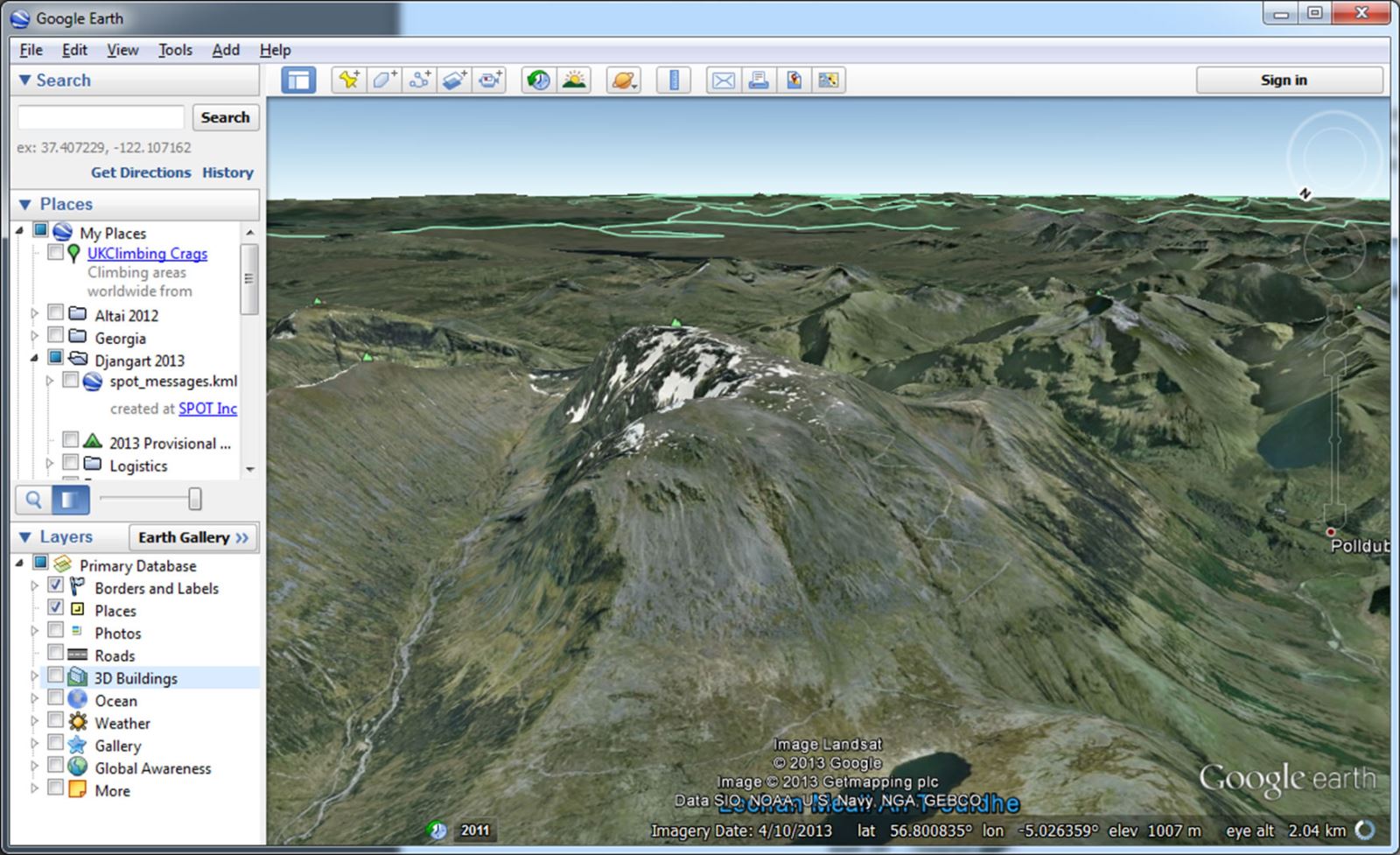

Google Earth, showing the tourist path up Ben Nevis

Fundamentally, Google Earth combines satellite images of the world, stretched down and overlaid onto a relief model of the earth’s terrain. It is a simple concept, but enables mountains and valleys to be reproduced with remarkable accuracy, as this example taken from a remote Kyrgyz valley shows:

Top: Image from a trip report by the Anglo-American 2010 Djangart expedition.

Bottom: The same view seen in Google Earth

Some of the nicest features of Google Earth include the ability to draw paths and inspect the elevation profile along the line (e.g. the walk-in for a glacial approach), see the time of year the photos were taken from (e.g. checking snow cover) and model the shadow cast by the sun onto the mountains (e.g. will the face will be in shade in the morning?).

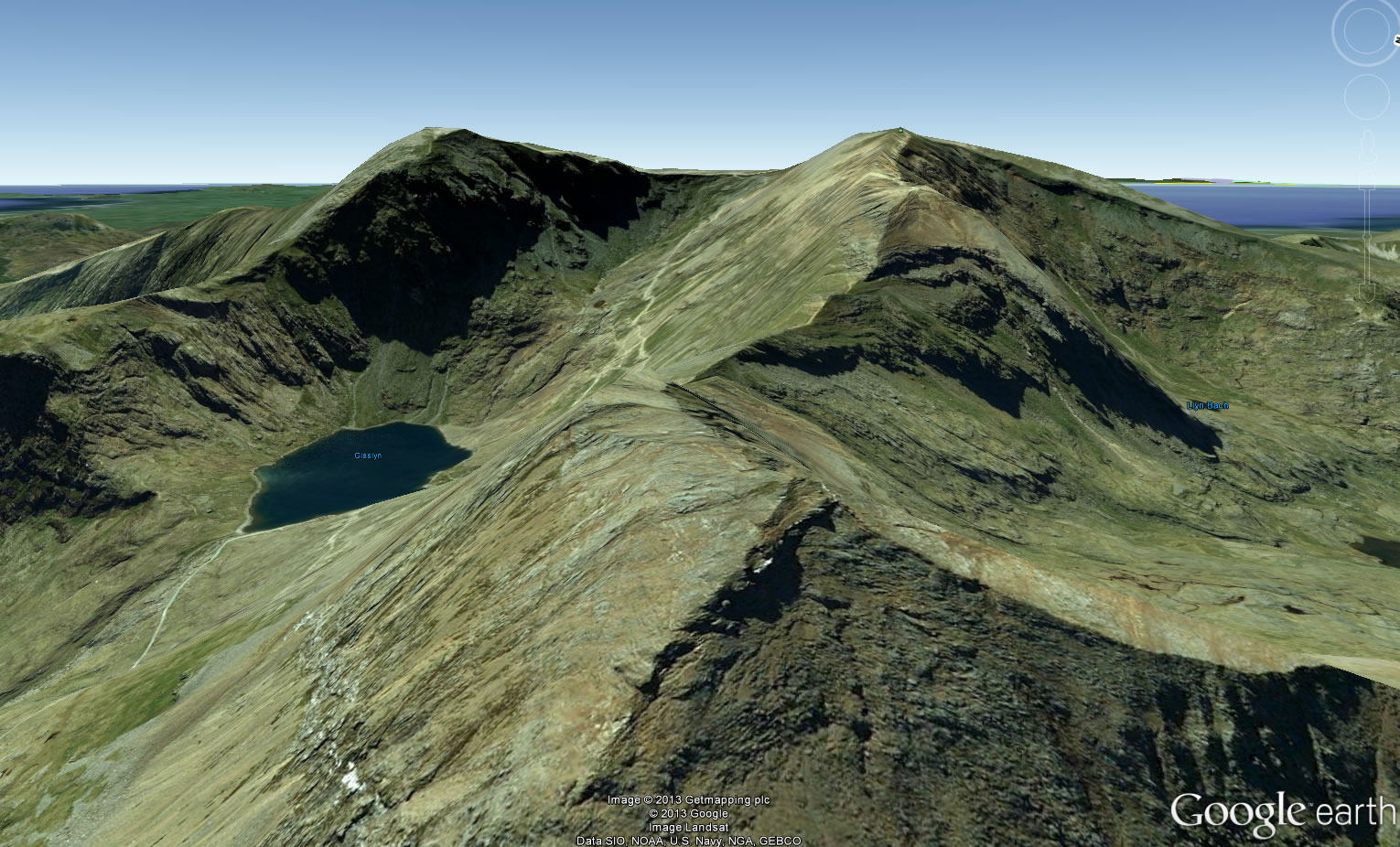

But a word of warning…there are some important caveats to this incredible wealth of relief data contained within Google Earth. Firstly, the topology loses accuracy in areas of sharp change of relief – take a look at Crib Goch or another famous ridge to see how benign they become. For the same reason, summit heights measurements should never be taken for granted.

The “knife-edge” ridge of Crib Goch, Snowdonia

More worryingly the data can sometimes be just completely wrong. The peak shown below lies on the Kyrgyzstan-Chinese border at just over 5000m, yet visit the same location in Google Earth and it doesn’t even exist.

Top: Photo from Bristol Djangart 2013 Expedition

Bottom: The same view seen in Google Earth - where is the peak?

Soviet Maps

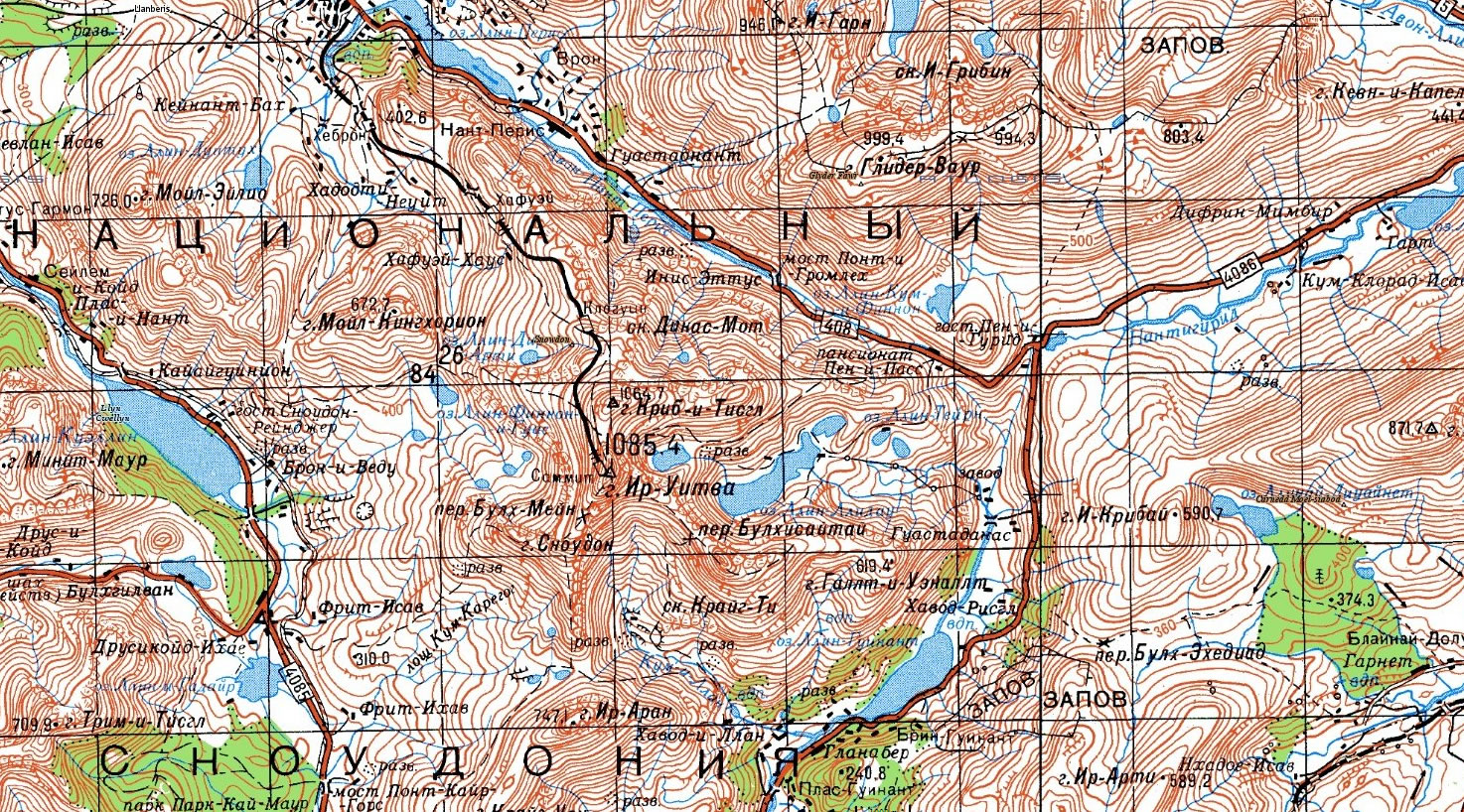

For much of the 20th Century, the Soviet Union invested huge resources into mapping large parts of the globe and today these maps still represent by far the best quality map you will find of many countries.

Soviet map of a valley system in Kyrgyzstan

To get hold of these online, the best place to start is

Topomapper, an easy to navigate and seamless stich of 1:100k (or better) topographic maps of the world.

If you're looking to access the original mapping sheets themselves, many organisations such as the Alpine Club maintain a small collection of the maps. However, the definitive source for downloading the original maps seems to be loadmap.net. The extent of the maps is phenomenal, from the mountains of South America to the passes of Snowdonia!

A Soviet map of Snowdonia!

Many of the maps were drawn by cartographers from satellite imagery so details may have changed in the last 30 years, particularly glaciers which seem to both retreat (due to global warming?) and advance (possible original cartographic errors?). Despite this the contours will give a remarkably accurate representation of the land as it is today.

Combining the two

To make best use of both data sets at once, Google Earth allows you to import an image overlay onto the map. A free download of any of the files from loadmap.net includes a small text file containing the latitude and longitude of the four corners of the map. You can use these to line up the map in Google Earth.

Soviet topographic map overlaid onto the Google Earth relief data

It is perfectly possible to head out on expedition and navigate by print outs from the Soviet maps and Google Earth. One of the few deficiencies in this approach is a lack of a sensible scale or GPS co-ordinates but both these problems are easy to solve by using a GIS package such as ArcGIS, although you may need to ask a friendly geographer to help you sort this out.

Ultimately, these maps won’t tell you where to climb but they do make it significantly easier to work out where to go before and after you arrive. Best of all, they are all free.

Want to find out more? Watch George's 'Using the map: Mountaineering and Technology' presentation where he describes how mountaineers are embracing the latest communications technology, such as Google Earth and Twitter.

Written by George Cave. George was a speaker at the BMC expedition planning seminar and is a member of the Bristol Djangart expedition 2013 which made seven first ascents on peaks along the Kyrgyzstan-China border in the summer of 2013.

« Back