Mountains have always meant more to humanity than just lumps of rock. We take a look at five summits with mysterious, magical or mythological significance.

Why climb a mountain? We all know George Mallory’s famously offhand answer to the question, but in reality there’s a lot more to it than that.

Human fascination with mountains long predates the era of modern mountaineering, and generations past have imbued them with all sorts of spiritual, mythological and symbolic significance. Stretching heavenwards, radiating primal power, they can easily be cast as the realm of deities, or allegories for the soul’s transcendence of the worldly realm.

Even avowed atheists can recognise that mountains mean more to us than just lumps of rock. The search for the profound and elemental, the groping towards self-improvement, the frisson of sublime danger; whatever your religious leanings, or lack of, it can be argued that climbing mountains meets a yearning in the human condition which shares many of the impulses behind spirituality.

So to mark May Day, that pagan festival of old, we thought we’d take a look at a small selection of mountains across the world with particular magical, mystical or mythological significance.

Pendle Hill, Lancashire

Pendle Hill from the Ribble Valley (Image: Charles Rawding, Geograph.co.uk)

Pendle Hill from the Ribble Valley (Image: Charles Rawding, Geograph.co.uk)

On a spring day in 1612, pedlar John Law was walking along a road near Colne in Lancashire when he was asked by a young woman called Alizon Device for some of his metal pins, the merchandise he was carrying from town to town. The pedlar refused. Moments later he fell to the ground, paralysed on one side. Alizon later confessed her guilt, saying a spirit in the shape of a black dog had appeared before her on the road, offering to punish the pedlar.

So began the chain of events which led to the Pendle witch trials. Four months later, along with nine others found guilty of using nefarious magic, Alizon would be hung to death on the moors near Lancaster. Another four centuries on, Pendle Hill, which looms over the Lancashire towns below with ominous energy, has become symbolic of the Pendle witches. Coincidentally, its name comes from a meshing together of the words for hill in three different languages – the Cumbric ‘pen’, the Old English ‘hyll’, with the modern English ‘hill’ added later.

In other words, it’s a triple tautology – and you know what they say about the number three.

Schiehallion, Perthshire

.jpg) Shiehallion poking above Perthshire hills (Image: Richard Webb, Geograph.co.uk)

Shiehallion poking above Perthshire hills (Image: Richard Webb, Geograph.co.uk)

Viewed from Loch Rannoch, the pyramidal shape of Schiehallion radiates significance; perhaps unsurprisingly, of all Scotland’s mountains, it is the one most richly draped in mystical and legendary associations.

Auspiciously positioned almost smack in the centre of the Scottish mainland, its name translates as the ‘Fairy Hill of the Caledonians’ – not your Disney-variety Tinkerbell types, but fiercely defensive supernatural beings prone to dragging those who intrude into their subterranean homes to the underworld. It’s also said to be a stomping ground for the Cailleach Bheur, the personification of winter in Irish and Scottish legend, a blue hag who freezes the landscape, fights the coming of spring and doles out icy death to unwary travellers (or ill-prepared hill walkers.)

Ironically for a hill so shrouded in mystical significance, it was also the site for a pioneering moment of science – a 1774 experiment led by Nevil Maskelyne to calculate the average density of the world. Not only was the resulting figure surprisingly near the mark, the experiment also gave rise to a discovery you see every time you peer at on Ordnance Survey map; while surveying the mountain to conduct measurements, Charles Hutton, a member of the expedition team, hit on the idea of contour lines.

Mount Prisank, Slovenia

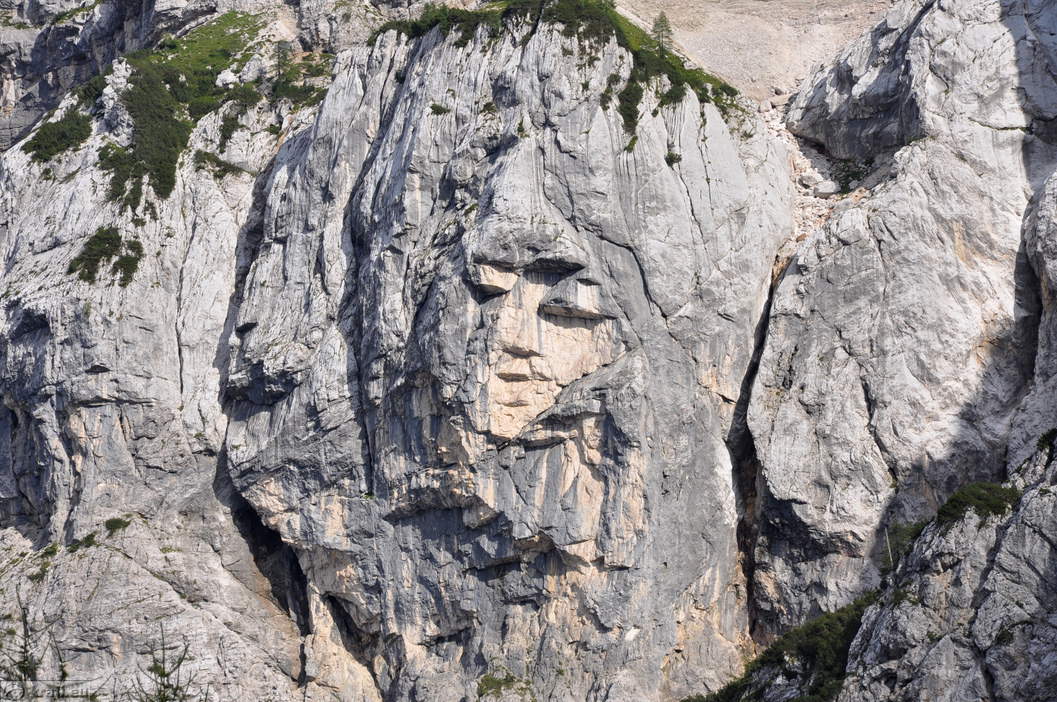

The 'Heathen Maiden', viewed from Erjavčeva koča (Image: DancingPhilosopher, Wikipedia)

The 'Heathen Maiden', viewed from Erjavčeva koča (Image: DancingPhilosopher, Wikipedia)

Humans are prone to seeing things in mountains – often abstract concepts like transcendence, sacredness or power. But on Mount Prisank, the thing in question is rather more literal. Ajdovska deklica, or the ‘Heathen Maiden’, is a rock formation said to bear a striking resemblance to a female face, albeit a slightly Picasso-esque rendering of one.

Local legend says a kind-hearted pagan giantess once prophesied the birth of a boy who would grow up to kill a golden-horned chamois, becoming rich in the process. Angered by the prophecy, her fellow maidens decided to punish her, and before she could say “don’t shoot the messenger,” they had rather harshly turned her into stone. Bad news for the maiden, but the good news for via ferrata fans is that a fine route now traverses the rock nearby.

Mount Athos, Greece

.jpg) Mount Athos (Image: Dave Proffer, Wikipedia)

Mount Athos (Image: Dave Proffer, Wikipedia)

The mythology behind Mount Athos’s creation is, literally, epic. Athos was a god who fought on the side of Chaos against the Olympians, led by Zeus. In a battle of Pacific Rim-like proportions, he lobbed a massive rock against Poseidon, which missed, landed in the Aegean Sea and became Mount Athos.

Despite this dramatic ancient Greek origin myth, the 2,030 metre (6,660 feet) mountain is now a place of great significance for Christianity. Cut off from the Greek mainland by a steep and narrow isthmus, Athos was well-situated for religious ascetics seeking retreat from the world, and following the establishment of a monastery in the ninth century was declared off-limits to laymen. Its divine status has survived the tumult of the intervening centuries (the mountain’s governing committee once even struck a deal with Hitler to prevent bombing) and is now home to 20 Eastern Orthodox monasteries in a self-governing region.

Accompanying this Christian heritage are Christian myths; the Virgin Mary is said to have walked ashore and marvelled: "Let this place be your inheritance and your garden, a paradise and a haven of salvation for those seeking to be saved"

Kailash, Tibet

Buddhist stupas, with Kailash in the background (Image: Yasunori Koide, Wikipedia)

Buddhist stupas, with Kailash in the background (Image: Yasunori Koide, Wikipedia)

Four of the longest rivers in Asia are fed from the slopes of Kailash, and four ancient religions hold it sacred.

For Hindus, its summit is home to Shiva the Destroyer. In Jainism, it neighbours a mountain where the first ‘Tirthankara’ achieved enlightenment. Buddhists believe it to be home to Buddha Demchok, who represents supreme bliss, and for followers of Bön, the Tibetan religion which predated Buddhism, the region in which it resides is the seat of all spiritual power. The 32 mile circumambulation of the mountain is a holy ritual, with some devotees even completing it while prostrating themselves at every step.

Kailash has never been climbed. Its north face, which looks over the Tibetan plateau, is a 6,000 feet high wall assessed by Hugh Ruttledge in 1926 to be “utterly unclimbable.” Its southern slopes are comparatively gentle, but religious awe and border politics have kept people from scaling them. Reinhold Messner was once offered the chance to make an ascent by the Chinese authorities, but refused. The chance was later offered to a Spanish team, but rescinded in the face of international disapproval. Messner commented: "If we conquer this mountain, then we conquer something in people's souls.”

Join online today by Direct Debit and save 25% on your first year's membership.

WATCH: What does the BMC do for hill walkers?

GET THE KNOWLEDGE: BMC resources for hill walkers

« Back